INTRODUCTION

In 2005, a French author named Giséle Littman published, under the pseudonym Bat Ye’or, a book entitled Eurabia – The Euro-Arab Axis. The text states that “ever since the early 1970s, the European Union was secretly conspiring with the Arab League to bring about a ‘Eurabia’ on the continent” (Bergmann 2021: 39). In 2011, another French author called Renaud Camus published a book entitled The Great Replacement, that “argued that European civilisation and identity was at risk of being subsumed by mass migration, especially from Muslim countries, and because of low birth rates among the native French people” (Ibid, 37). Even though these books may have introduced the “fear of cultural subversion”, the full conspiracy theory “usually also takes the form of accusing a domestic elite of betraying the ‘good ordinary people’ into the hands of the external evil” (Ibid, 38).

How, then, can we define the Eurabia conspiracy theory in concise terms? First, let us take a step back and look into the definition of conspiracy theory, in a more general sense: Conspiracy theory can be defined as a representation in the form of a narrative that explains an event or circumstance as being the result of a group of people with covert and malicious intentions (adapted from Leone et al. 2020: 44 and Birchall 2006: 34). From this, the definition of the Eurabia conspiracy theory may thus be: the European continent is being transformed into an Islamic society through the destruction of white Christian civilisation, brought about by the secret alliance between Muslims, the domestic elites of Europe, and left-wing cultural-Marxists (adapted from Bergmann 2021 and Gualda 2021). This conspiracy theory in particular “has been one of the most fast-growing amongst Neo-Nationalists, rooting in countries like Austria, Denmark, Germany, Italy”, the UK, the Netherlands, and Belgium (Bergmann, 2021: 37).

Given the relevance of this topic, this short exploratory presentation aims to semiotically analyse the messages from a white supremacist Telegram group, with the help of digital humanities methodologies, seeking language patterns that can potentially assist in the codification of cultural meanings and in the formation of these anti-Muslim ideological clusters on Telegram. This presentation regards work that is still in-progress, as I am nearing the end of my first year of the PhD course.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unfortunately, I am unable to share the name of the Telegram group from which I obtained my data, as it is sensitive information protected by the GDPR.

The data that I obtained from the group was the textual (non-pictorial) content of messages sent from its administrator to the channel’s subscribers (which are a total of 12.5 thousand accounts). The messages were collected from October 1st to December 31st, 2023, manually (one by one), totalling 168 messages. My intention is to automate this process in the future. Seeing how this was my first test, I thought it would suffice to collect this amount manually for now.

The data was compiled on a .txt file, which was then uploaded to Voyant – an open-source web-based text reading and analysis environment which was designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars.

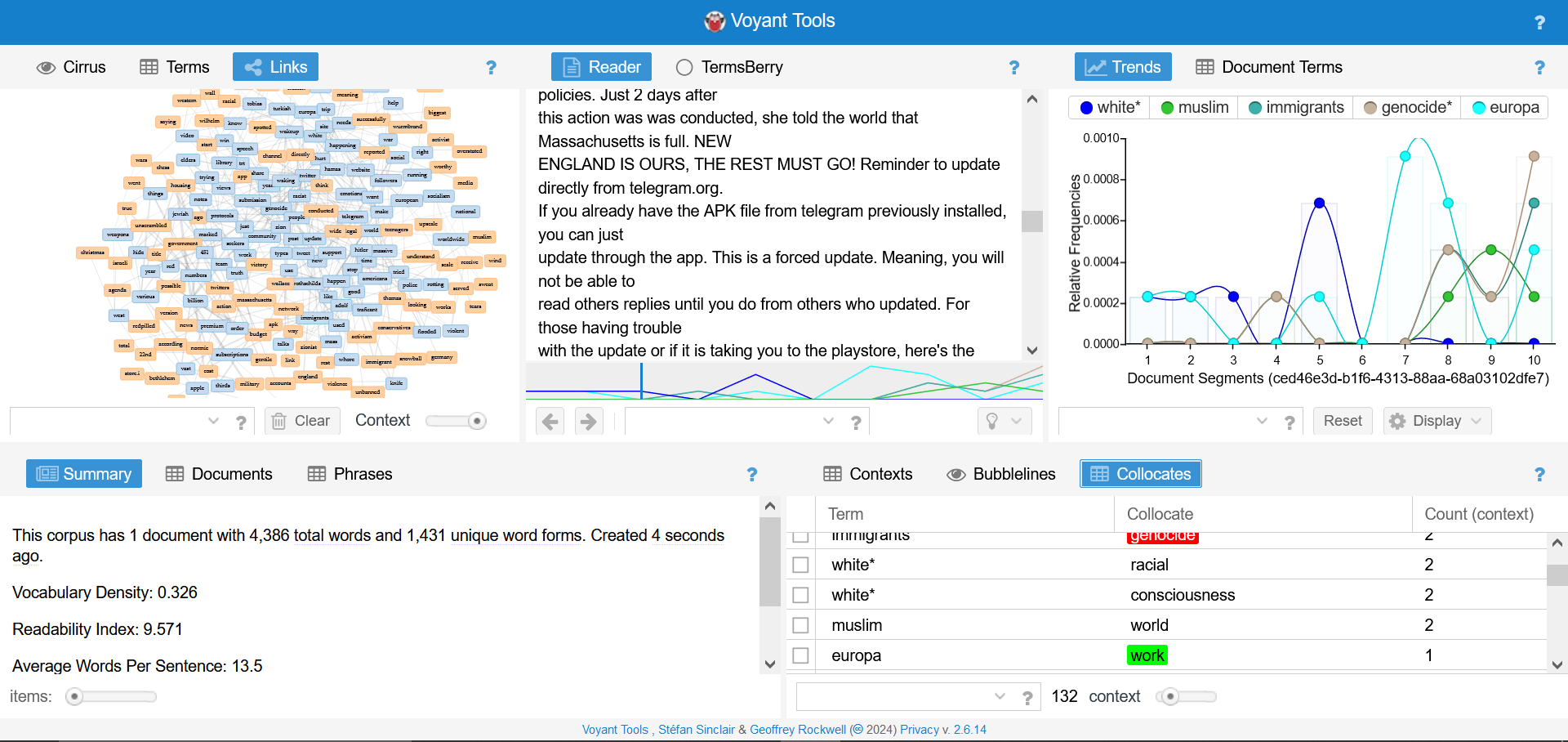

After uploading the file to Voyant, this is the control panel that I was working with:

PRELIMINARY RESULTS

I explored some of Voyant’s available tools that could help me in identifying language patterns, starting with the ‘Collocates’:

The ‘Collocates’ list provides the terms that occur near certain keywords. The highlighted words – for example “genocide”, “work”, “victory”, “run” – are built-in categories from Voyant, that serve to classify words “positive” (green) and “negative” (red). Voyant allows you to edit those categories, but since I am not doing sentiment analysis, there was no need to consider them for now. Even so, it may be interesting to see how “immigrants” are mostly associated with words such as “genocide”, “threats”, and “run”, while the word “white” appears together with “work” and “victory”. Other relevant associations may be the collocates: “white” + “replacement”; “genocide” + “Europeans” + “Europe”; “immigrants” + “tax” + “payer”; and “immigrants” + “illegals”.

With this first list only, it is already possible to see how one does not need to read all 168 messages in order to get a picture of the discourse contained in this Telegram group, which I believe to be the point of such tools – to facilitate analysis of large datasets.

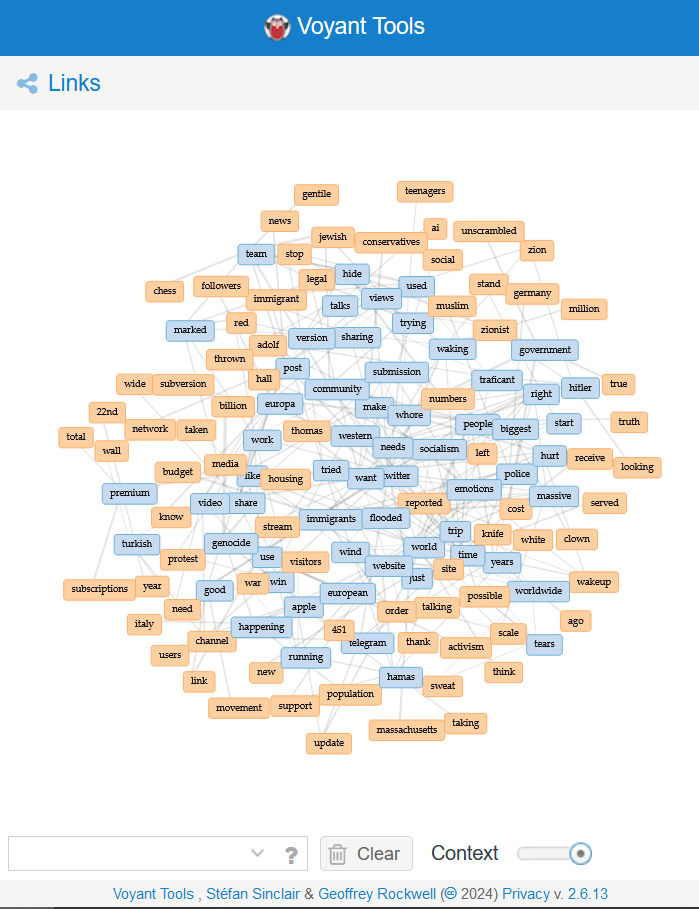

Moving on to the next panel (below), it is possible to see the most common words of the file, and if one hovers the mouse over a term, the terms that occur near to that word are highlighted. This provides for better visualisation, since it allows one keyword to be related to more than just one other term, like in the previous table. In turn, each of such terms is further related to other collocates, forming a web of most common keywords and the most common terms found near them in the text.

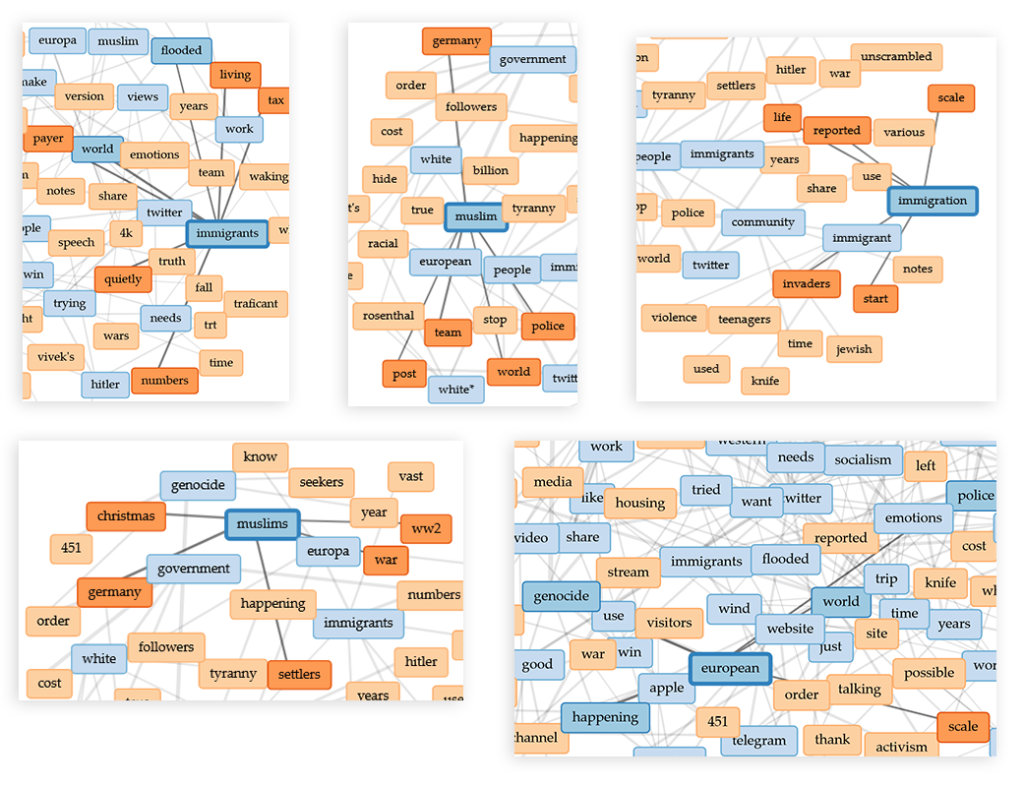

I highlighted a few segments that seemed most relevant:

The first one surrounds the word “immigrants”, which is linked to, again, ‘tax’ and ‘payer’, but also to ‘living’, ‘quietly’, and ‘numbers’. The word ‘quietly’ points to the conspiratorial nature of the immigration phenomenon, implying that there is a secret agenda behind it.

The next image centres around the word ‘muslim’ (in singular), which is here linked to ‘germany’, ‘team’, ‘police’, ‘post’, and ‘world’. This data is a bit harder to interpret. We know from the image on the left bottom corner that ‘hitler’ is also one of the most popular terms used in the Telegram group, and considering how this is a white supremacist group, it is unsurprising that Germany gets many mentions, given the country’s history with such movements. Yet, terms like ‘team’, ‘post’, and ‘world’ do not provide for clear analytical results.

The third image (on the upper right), centres around the term ‘immigration’, which is linked to ‘scale’, ‘life’, ‘reported’, ‘invaders’, and ‘start’. Here, we have a clearer picture of the discourse, especially with the word ‘invaders’, which is also connected, in its turn, to ‘jewish’ and to ‘knife’.

On the bottom left corner, we have the web surrounding the word ‘muslims’ (in plural), linked to ‘christmas’ (I collected the messages during the month of December, so it makes sense), ‘ww2’, ‘war’, ‘settlers’, and again ‘germany’. In this case, perhaps ‘settlers’ is the most significant meaning-making term.

Finally, regarding the word ‘european’, we may see ‘genocide’, ‘happening’, ‘world’, ‘police’, and again ‘scale’. It is important to point out that ‘genocide’ is here linked to ‘european’, not with ‘muslim’. However, we saw from the collocate list that it can also be found near the word ‘immigrant’, despite it not showing in this visualization form.

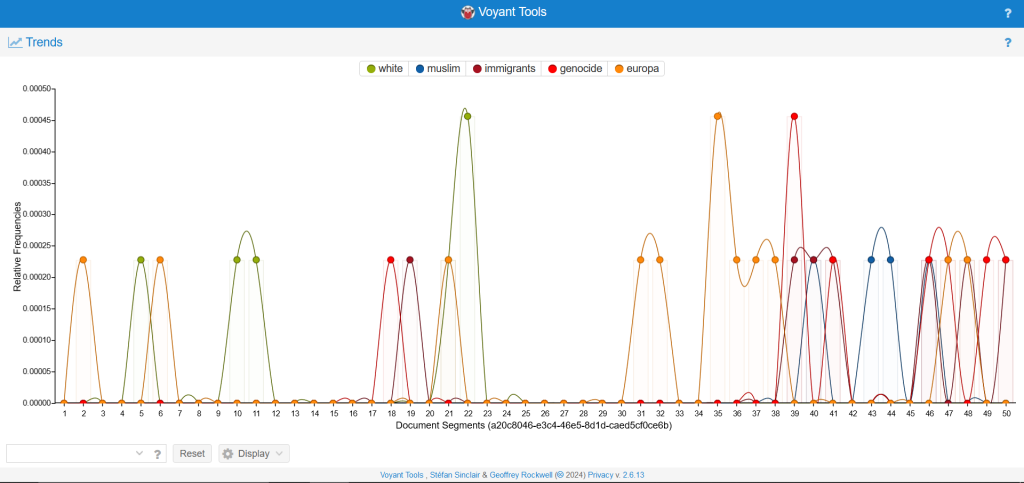

Lastly, I would also like to share results obtained from the ‘Trends’ tool, which offered me the following graph:

It measures the occurrence of these selected terms over the course of the manuscript, and since the file contains the messages in order of post, it also reflects passage of time. The extreme left represents the start of October while the right represents the end of December. Here, it is interesting to note how the term ‘muslim’ only appears at the end, and in a couple of curves (around segments 38 to 47 – probably around November) it coincides with occurrences of the term ‘immigrants’ and ‘genocide’. However, from previous analysis, we see that ‘genocide’ is not a collocate of ‘muslim’, but it may be of ‘immigrant’ and surely is of ‘european’. This graph indicates that terms appear roughly in the same segment of the document, but not necessarily in the same sentences. Besides, the fact that the term Europa appears throughout the document is also important to consider, which makes it hard to interpret these curves as meaningful.

DISCUSSION

According to the literature, in Eurabia and Great Replacement discourses, ‘Islam’ is associated with “evil, crime and barbarism”, as well as other “harmful characteristics and ideological markers that enhance polarised, emotional and simplifying visions of social reality” (Gualda 2021: 57). It is “typically represented as backwards, fanatic and violent”, as well as a totalitarian political doctrine (Dyrendal 2020: 374), while Muslims themselves “are generally portrayed as a homogeneous group of violent and authoritative religious fundamentalists” (Bergmann 2021: 42). Muslim individuals are seen as “mere executors of a religiously based, collective will” and, consequently, since Islam is itself seen as fundamentalist in nature, “every believer will be made to follow its radical version” (Dyrendal 2020: 374). In this sense, the idea of ‘Islam’ is seen as being a uniting factor for all Muslims, that unites them “in a common plan for domination” (Ibid).

In this sense, the “Eurabia conspiracy theory has often become entangled in a more general opposition to immigration” (Bergmann 2021: 40), connected to political statements of failed integration (Ekman 2022: 1128) – which are based around the notion that Western societies are homogeneous, and that Muslims and other migrants are unable to integrate into them (Gualda 2021; Ekman 2022) – or to the notion that “incorporation of diversity, multiculturalism or other elements of Islam or the Muslim world into [Western] culture” will mean the total collapse of society, which will become a colony of Islam (Gualda 2021: 61-62). In other words, the arrival of “new norms, habits and customs brought by the foreign population […] could influence the disappearance of one’s own culture” (Ibid), turning immigration into an ‘invasion’ that threatens people’s culture and identity – as it was possible to see from the results of the quantitative analysis, which pointed to how ‘muslims’ and ‘immigrants’ are often linked to terms such as ‘invaders’ and ‘settlers’.

In general, the Eurabia conspiracy theory was brought firmly into the political mainstream by the financial crisis of 2008 and later the refugee crisis of 2015 (Bergmann 2021: 48-49). Nowadays, it is common to find political leaders who propagate Great Replacement and/or Eurabia conspiracy theories (Ekman 2022: 1127). As we see such Islamophobic and anti-immigration radical discourses become more popular, we also see them become normalized, especially across new media platforms such as Telegram.

CONCLUSION

As means of conclusion, considering this work is still in-progress, I can point to how automatization is dearly needed for such research – the more data, the more accurate the analysis. Another issue is that there are limits to how much semiotic analysis can be done on top of these quantitative results; how much can actually be accurately interpreted from these lists, graphs, and flowcharts? So much of semiotic analysis depends on context, therefore it is still hard to see how we can carry out analysis in large scale without losing said context. Nevertheless, I still believe there is much need for the development of such methodology, since when it comes to social media, scholars need to work with increasingly larger texts.

REFERENCES

Bergmann, E. (2021). The Eurabia conspiracy theory. In: Önnerfors, A., & Krouwel, A. (Eds.), Europe: Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe. Routledge, 36-53.

Birchall, C. (2006). Knowledge goes pop: From conspiracy theory to gossip. Berg Publishers.

Dyrendal, A. (2020). Conspiracy Theory and Religion. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 304-316.

Ekman, M. (2022). The great replacement: Strategic mainstreaming of far-right conspiracy claims. Convergence, 28(4), 1127-1143.

Gualda, E. (2021). Metaphors of Invasion, Imagining Europe as Endangered by Islamisation. In: Önnerfors, A., & Krouwel, A. (Eds.), Europe: Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe. Routledge, 54-75.

Leone, M., Madisson, M., & Ventsel, A. (2020). Semiotic Approaches to Conspiracy Theories. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 43-55.