Extremism prevention work that focuses on universal or the overlap of universal and selective pedagogical prevention often relies on the development and implementation of workshop formats (Ceylan & Kiefer, 2022; Slama & Kemmesies, 2020). These workshops address diverse participants in a group setting, ranging from students in schools to multipliers like teachers in training, social workers, and police or prison officers. During implementation, various forms of resonance are generated (Koynova et al., 2022). Such feedback can serve as a tool for the iterative formative assessment of the implementation process, helping facilitators adjust and improve workshops dynamically (Golding & Adam, 2016; Husain & Khan, 2016). Unlike evaluation, this monitoring offers a descriptive overview of the current state of implementation (Junk, 2021; Koynova et al., 2022).

During my secondment at the Violence Prevention Network (VPN), I worked on a project aimed at refining feedback tools to better fit the demands of prevention practice and enhance their potential for monitoring processes. To achieve this, we collaborated closely with practitioners, incorporating their perspectives and experiences while following a procedure inspired by design thinking (Meinel et al., 2011). This iterative, practice-oriented approach enabled us to systematically analyze the needs of practitioners, identify challenges in feedback collection, and refine tools through testing and incremental adjustments. In line with previous reports, core concerns included limited time, personnel, and financial resources (Koynova et al., 2022). Thus, when designing the feedback tools, time efficiency, integrability into the course of the workshop, and quick and simple documentation were mainly considered (s. also Junk, 2021). In this light, this blog post summarizes the background and development of the project, exploring how feedback can best be used for monitoring in universal and selective prevention contexts.

Across disciplines, feedback is generally understood as information about how something is perceived (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2010; Jug et al., 2019; Voyer et al., 2016). In the context of extremism prevention, the possibilities and use of feedback can vary between individual counseling, typically employed in selective or indicated prevention, and group settings, which are more common in universal or selective prevention (Flückiger, 2021; Slama & Kemmesies, 2020). While the sender and receiver of feedback can also vary, the focus here lies on feedback provided by participants during workshops and how it can inform processes of adapting and developing the programs accordingly. Asking for participant feedback aligns well with the goals of prevention, fostering democratic practices and valuing participants’ opinions. In some settings, such as prisons or schools with strict regulations, it may be unusual for participants to be asked about their impressions (Witt, 2006). Feedback in workshops is predominantly understood as an assessment of the quality of the training and participants’ satisfaction. However, additional aspects can be considered when gathering participant feedback, such as changes in experiences, attitudes, and needs (Jacobs et al., 2010; Sufi Amin et al., 2020).

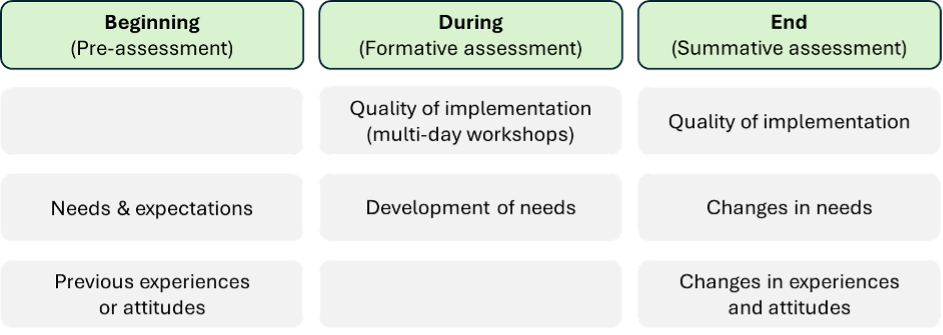

To enhance practical applications, universal/selective prevention workshops taking place in different contexts were observed in a first step. Many workshops already incorporated elements of participant resonance, such as introductory or final rounds that encourage participants to share associations, wishes, or experiences. Feedback elements can directly impact the composition of the current or a subsequent workshop and allow for follow-up reflections. This indicates that depending on when and how feedback is collected, different conclusions can be drawn. Consequently, observations led to a systematization of the different aspects, considering the course of a workshop (see Table 1). While a final feedback round captures retrospective assessments, it may overlook new needs that emerged during the workshop. In contrast, pre-post feedback distinguishes between participants’ initial expectations and their concluding insights.

Table 1. Overview of possibilities of feedback methods over the course of a workshop

In the next phase, the existing feedback instruments were refined and complemented to facilitate the monitoring of workshops. While feedback is already a common element of workshop formats, small adjustments can help implement, structure, and document feedback sequences more systematically. Feedback tools were structured by implementation timing (beginning, middle, or end of the workshop) and the type of response they generate. In this regard, they were tailored to align with the goals of the workshop formulated beforehand. Additionally, the feedback formats were designed to integrate smoothly into the overall workshop structure to minimize time constraints often expressed by practitioners while also enabling and encouraging different participants to express feedback.

As open-ended feedback questions are common practice in oral introductions and final rounds, this approach was maintained to capture both intended and unintended effects of the workshop, which are essential for monitoring efforts (Koynova et al., 2022). Open-ended questions also encourage references to specific experiences and examples, avoiding overly general statements such as “everything was great.” This approach provides insights into overall satisfaction, as well as the development of needs and experiences, including: What did participants want to remember from the workshop? Which questions were relevant at the beginning? Which new questions arose during the workshop? What topics concern the group? How did attitudes shift over time?

Workshops with trainers who tested preliminary feedback tools revealed the need for two different approaches. Although the scope is similar, younger participants require pedagogically engaging methods, whereas adult participants can be asked more directly through open-ended questionnaire formats. Given the different insights that can be gained from feedback, these different formats were incorporated into a modular framework that enables flexible combinations of feedback methods depending on available time and workshop dynamics. For each method, options for online or offline implementation were designed, allowing for anonymous responses. While online tools simplify data collection, analog formats need to be photographed and compiled at the end. Additionally, participant preferences and potential barriers to either format need to be considered. A structured documentation archive that traces feedback back to specific workshops, target groups, and settings is crucial for clustering responses and making necessary adjustments.

In conclusion, a well-structured feedback system can enable practitioners to identify recurring needs, refine content, and track the demands of specific target groups. Instead of using feedback solely for isolated session assessments, a systematic approach allows for long-term insights into learning experiences and trends across multiple workshops. This ensures that prevention programs remain dynamic and responsive to participant needs.

Bibliography:

Ceylan, R., & Kiefer, M. (2022). Chancen und Risiken der Radikalisierungsprävention. In R. Ceylan & M. Kiefer (Eds.), Der islamische Fundamentalismus im 21. Jahrhundert (pp. 289–301). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-37486-0_14

Flückiger, C. (2021). Basale Wirkmodelle in der Psychotherapie: Wer und was macht Psychotherapie wirksam? Psychotherapeut, 66(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00278-020-00478-y

Golding, C., & Adam, L. (2016). Evaluate to improve: Useful approaches to student evaluation. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.976810

Husain, M., & Khan, S. (2016). Students’ feedback: An effective tool in teachers’ evaluation system. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research, 6(3), 178. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-516X.186969

Jacobs, A., Barnett, C., & Ponsford, R. (2010). Three Approaches to Monitoring: Feedback Systems, Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation and Logical Frameworks. IDS Bulletin, 41(6), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00180.x

Jug, R., Jiang, X. “Sara,” & Bean, S. M. (2019). Giving and Receiving Effective Feedback: A Review Article and How-To Guide. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 143(2), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2018-0058-RA

Junk, J. (2021). Quality management of P/CVE interventions in secondary and tertiary prevention: Overview and first steps in implementing monitoring and reporting.

Koynova, S., Mönig, A., Quent, M., & Ohlenforst, V. (2022). Monitoring, Evaluation und Lernen: Erfahrungen und Bedarfe der Fachpraxis in der Prävention von Rechtsextremismus und Islamismus. Peace Research Institute Frankfurt. https://doi.org/10.48809/PRIFREP2207

Meinel, C., Leifer, L., & Plattner, H. (Eds.). (2011). Design Thinking. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13757-0

Slama, B. B., & Kemmesies, U. (Eds.). (2020). Handbuch EXTREMISMUSPRÄVENTION.

Sufi Amin, Prof. Dr. Samina Malik, & Prof. Dr. N. B. Jumani. (2020). Exploring Socialization Process, Peacebuilding and Value Conflict of Distance Education Students at International Islamic University Islamabad. Sjesr, 3(3), 198–203. https://doi.org/10.36902/sjesr-vol3-iss3-2020(198-203)

Voyer, S., Cuncic, C., Butler, D. L., MacNeil, K., Watling, C., & Hatala, R. (2016). Investigating conditions for meaningful feedback in the context of an evidence-based feedback programme. Medical Education, 50(9), 943–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13067

Witt, K. (2006). Feedback-Kultur als Strategie demokratischer Veränderung. Fontane-Gymnasium Rangsdorf, Brandenburg (pp. 37, [22] pages). BLK : Berlin. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:197