INTRODUCTION

White Genocide conspiracy theories surround the notion that native white people of predominantly white countries are being dis/replaced with alien people of colour as a result of a hostile alliance between domestic and foreign political-economic elites. This idea has been traced all the way back to pre-World War II, with antisemitic conspiracy theories narrating the existence of a Jewish plot to destroy Europe through miscegenation, having deep historical roots in French nationalism (Davis 2025), especially with the book The Uprooted (1897) by Maurice Barrès. In the XIX century, it was common for nationalist politicians to compare France’s low birth-rate with the high birth-rates of East-Asian countries of that time (Anderson 2014). From such negative comparisons, the fear of Asian mass-migration arose. More recently, scholars often cite the book The Great Replacement (2011) by another French author called Renaud Camus as a relevant contribution to the conspiracy theory, this time targeting Muslims and other migrants from North Africa and the Middle East (Bergmann 2021).

In general, White Genocide conspiracy theories highlight the fear of cultural subversion, accusing a domestic internal elite of betraying the native white people into the hands of an external evil. Intrinsically tied with ani-immigration discourses, these conspiracy theories presuppose three states: First, a paradisical past; the Good Old Days when Europe/North America were only populated by Caucasians (at least in the interpretations of these conspiracy theorists). Then, a present danger; white people are disappearing due to immigration and low birth rates. And lastly, the envisioning of a better future; plans for making Europe/North America return to their supposed cultural, ethnic, and religious roots.

In concise terms, conspiracy theory can be defined as a representation in the form of a narrative that seeks to explain a determined circumstance as being the result of a secret plan implemented by a morally evil group of people that, if left unstopped, will lead to catastrophe (adapted from Birchall 2006 and Önnerfors 2021). From this, the definition of the White Genocide conspiracy theory may be that there is scheme by political and economic elites in predominantly white countries to cause the extinction of what are perceived as native white populations through the promotion of miscegenation, multicultural and racial integration policies, mass immigration, low fertility rates and abortion of native people, and organised violence (adapted from Jackson 2015 and Davis 2025).

The aim of this research is to identify language patterns that can potentially assist in the semiotic modelling / codification of cultural meanings and in the formation of white-supremacist ideological clusters on social media. The research question that guides this study is: What types of signs, texts, and codes structure the White Genocide conspiracy theory?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unfortunately, even though the Telegram channel itself is public, I am unable to share its name as it is sensitive information protected by the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The data that I obtained from the channel was the textual (non-pictorial) content of messages sent from its administrator to the channel’s subscribers (which amount to more than 22 thousand accounts). The messages were collected from January 1st, 2023, to December 31st, 2024, totalling more than 4 thousand messages, varying in length.

The method of analysis is still being developed. I am working in partnership with the Computational Linguistics department of the University of Turin to refine available tools for the analysis of right-wing conspiracy theories. We are applying what is called Semantic Annotation with Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (LIWC) using the vocabulary from the Moral Foundations Dictionary (MFD). I will explain shortly how this works.

ANNOTATION PIPELINE

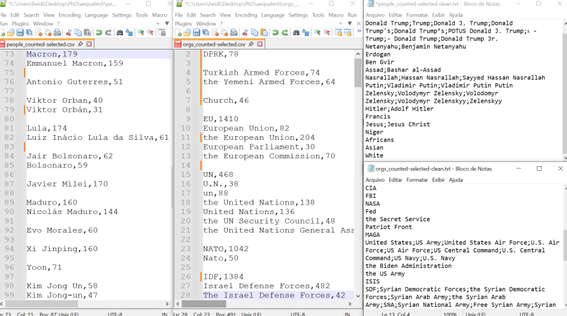

The first step was the entity selection – that is, choosing specific instances (people and organizations) that are interesting subjects of discourse. Basically, I was looking for specific texts potentially discuss certain topics of interest for analysis. The software is able to identify people and organizations on itself, however it does not understand that, for instance, UN and U.N. are the same thing. Therefore, when I was selecting the subjects of interest, I had to also compile the different ways that the same person/org could show up in the dataset, as you can see in this screenshot I took.

On the left, there are the outputs that the software automatically generated and on the right there are my list of interesting entities and how they may appear. After making a list of interesting entities, we generated random samples for annotation. Three sets (for 3 annotators) of 400 messages (each) were randomly assembled from the total of all texts containing the selected entities. This way, each annotator would be able to read and annotate a set of 400 messages. But what does annotating actually mean?

Simply put, text annotation is adding a tag to a text excerpt. Basically, we are teaching the computer to understand which terms and expressions have similar semantics and share common contexts so that they can be represented in space close to each other or have the same representation. This way, meaning is approximated so that words can be represented in a lower dimensional space.

The idea is that, once the dataset is annotated, LIWC will able to – for a given text input – return output lists of words falling into each category. These are the meaningful that we are mapping:

- pronouns – first-person / third-person / singular / plural

- ingroup-outgroup language – us vs. them; native vs. alien/foreign; white identity vs. racial resentment

- concerns- work, leisure, home, money, death…

- time orientation – past, present, future + sentiment polarity in relation to time – negative view of the present / positive view of the past? What about the future?

- affective processes – positive emotions (joy, safety, celebratory feelings, trust…); negative (anxiety, anger, disgust, sadness, fear); and neutral (anticipation, surprise…)

With those interests in mind, the third step was the definition of the taxonomy, that is, deciding on specific categories to annotate the texts with. These are the categories that I came up with, believing them to be useful for analysis of conspiracy theory structure:

- enemy / out-group / them

- victims

- in-group / us

- evil plan / evil deed

- mis/disinformation

- glorified past / reactionary

- fear of the future

- danger of the present

For instance, in a given text we have “concerned citizens” as the in-group. Then, we have the sentence that states that “activism today quickly turns violent” in contrast with the idea that this was not the case with activism in the past (danger of the present). The sentence “issues ignored by the mainstream” indicate that these problems are secret, conferring the conspiratorial aspect to the text. On another text, the ‘evil plan / evil deed’ category is labelled onto a sentence stating “loss of 1.3 million more jobs while foreign-born workers gained more than 1.2 million.” Also the expression “erasing your existence” has been found to be very telling of the White Genocide conspiracy theory in these texts.

FINAL REMARKS

But so far I’m confident that this is a good way to help scholars to quickly gain insights from these huge datasets. This white supremacist channel does not only disseminate White Genocide conspiracy theories, but by teaching the computer to understand and summarize what are the out-groups, in-groups, victims, evil plans, present danger, and fear of the future for each text, one can easily paint the picture of the main structure of a conspiracy theory narrative, allowing scholars to not just identify their presence in a dataset, but also understand their main elements and how they are related, without having to go through the whole textual content. Since we’re still developing this, I cannot say with 100% certainty that it will work, but I believe in the relevance of trying. And if it doesn’t work, at least I’ll have a map of why it didn’t work and how future research may develop better ways to do this same thing.

REFERENCES

Anderson, M. C. (2014). Regeneration Through Empire: French Pronatalists and Colonial Settlement in the Third Republic. University of Nebraska Press. p. 25.

Bergmann, E. (2021). The Eurabia conspiracy theory. In: Europe: Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe. Routledge, 36-53

Davis, M. (2025). Violence as method: the “white replacement”, “white genocide”, and “Eurabia” conspiracy theories and the biopolitics of networked violence. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 48(3), 426-446.

Jackson, P. (2015). ‘White genocide’: Postwar fascism and the ideological value of evoking existential conflicts. In The Routledge history of genocide (pp. 207-226). Routledge.

Birchall, C. (2006). Knowledge goes pop: From conspiracy theory to gossip. Berg Publishers.

Önnerfors, A. (2021). Conspiracy theories and COVID-19: The mechanisms behind a rapidly growing societal challenge. Myndigheten för Samhällsskydd och Beredskap.