INTRODUCTION

Most authors agree that the Eurabia conspiracy theory started with the publication of the book entitled Eurabia – The Euro-Arab Axis, in 2005, by a French author named Giséle Littman, but published under the pseudonym Bat Ye’or. The text states that “ever since the early 1970s, the European Union was secretly conspiring with the Arab League to bring about a ‘Eurabia’ on the continent” (Bergmann 2021: 39). In 2011, another French author called Renaud Camus published a book entitled The Great Replacement, that “argued that European civilisation and identity was at risk of being subsumed by mass migration, especially from Muslim countries” (Ibid, 37). These books introduced the “fear of cultural subversion” that is characteristic of this conspiracy theory.

Eurabia also presuppose three states: First, a paradisical past when Europe was only populated by Caucasians (at least in the interpretations of these conspiracy theorists). Then, a present danger which configures a fall from paradise; white people are disappearing due to immigration and low birth rates of ‘native’ Europeans. And lastly, redemption, the envisioning of a better future; plans for making Europe return to its supposed cultural, ethnic, and religious roots.

My research aims to semiotically analyse the messages from a white supremacist Telegram group, with the help of digital humanities methodologies, seeking language patterns that can potentially assist in the codification of cultural meanings and in the formation of these anti-Muslim ideological clusters on Telegram. The main contributions of my work to the filed of Semiotics is the incorporation of computational tools in the analysis of text in large-scale (allowing for both data size and data depth), and the contribution to Digital Humanities is to go beyond only the detection of conspiracy theories in online content but towards structural analysis without sacrificing context, which is a big problem in the field of computational tools applied to humanities and social sciences research nowadays.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Unfortunately, even though the Telegram channel itself is public, I am unable to share its name as it is sensitive information protected by the GDPR. The data that I obtained from the channel was the textual non-pictorial content of messages sent from its administrators to the channel’s subscribers (which amount to more than 22 thousand accounts). The messages were collected from January 1st, 2023, to December 31st, 2024, totalling more than 4 thousand messages, varying in length.

The method of analysis is still being developed. We are applying what is called Semantic Annotation with Linguistic Inquiry Word Count using the layout of FrameNet (a lexical database being developed at the International Computer Science Institute in Berkeley since 1997).

Simply put, text annotation is adding a tag to a text excerpt. Basically, we are teaching the computer to understand which terms and expressions have similar semantics and share common contexts so that they can be represented in space close to each other or have the same representation. This way, meaning is approximated so that words can be represented in a lower dimensional space.

The first step in the annotation process was the entity selection – that is, choosing specific instances (people and organizations) that are interesting subjects of discourse. Basically, I was looking for specific texts that potentially discuss certain topics that are of interest for analysis.

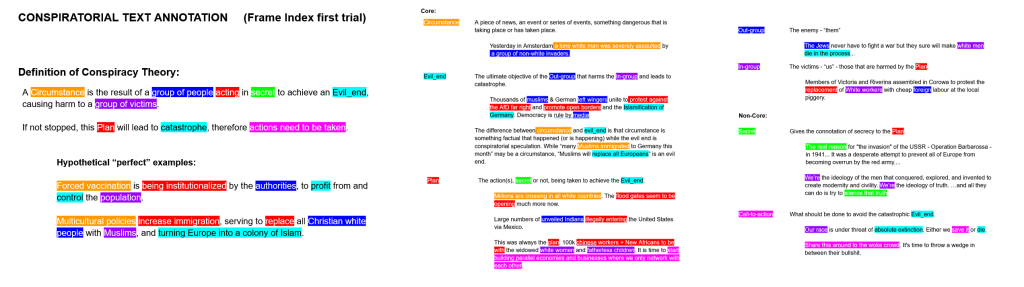

The next step was the definition of the taxonomy, focusing on the core-elements of a conspiracy theory. Basically this means deciding on the specific categories to annotate the texts with. Initially, we accessed the FrameNet database and found that they do not have an annotated dataset for “conspiracy” – which is excellent, since this is what we are trying to make. Instead, they give the “closest” results which are: Collaboration and Offense. Using these 2 as examples, I developed the Frame Index for Conspiracy Theory. After making a list of interesting entities and having the well-defined taxonomy, we generated random samples for annotation.

A scheme of the developed Fame Index can be found on the image below:

Obviously, each text will, most of the time, present only a few of these categories, which is fine. If the software can learn to flag the excerpts that have 2 or 3 of these tags, they can go into the “to be analysed by a human” box. This could be a way to use computation to make human analysis more efficient. By separating the “useful” extracts for analysis and displaying them with the pre-identified tags, then, a deeper discourse analysis can be carried out by the semiotician.

We are still in the annotation process which means I do not have the results from the computational analysis yet. But so far, I’m confident that this is a good way to help scholars to quickly gain insights from these huge datasets. This white supremacist channel does not only disseminate Eurabia conspiracy theories, but by teaching the computer to understand and summarize what are the out-groups, in-groups, evil plans, for each text, one can easily paint the picture of the main structure of a conspiracy theory narrative, allowing scholars to not just identify their presence in a dataset, but also understand their main elements and how they are related, without having to go through the whole textual content, which would be quite time-consuming, not to mention emotionally exhausting due to the pernicious character of these messages’ content. Since we’re still developing this, I cannot say with 100% certainty that it will work, but I believe in the relevance of trying.

DISCUSSION

Now, to close up, I would like to discuss the Religion problem, since this is the European Academy of Religion congress. The last time I presented this case study at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, I had interesting feedback. People were asking me “Why are you treating this conspiracy theory as a religious one? It’s not religious, it’s political”. So, I thought that this conference would be a good opportunity to present my take and see what do other scholars from religious studies think of this issue.

According to the literature, in Eurabia and Great Replacement discourses, ‘Islam’ is associated with “evil, crime and barbarism”, as well as other “harmful characteristics and ideological markers that enhance polarised, emotional and simplifying visions of social reality” (Gualda 2021: 57). It is “typically represented as backwards, fanatic and violent”, as well as a totalitarian political doctrine (Dyrendal 2020: 374), while Muslims themselves “are generally portrayed as a homogeneous group of violent and authoritative religious fundamentalists” (Bergmann 2021: 42). Muslim individuals are seen as “mere executors of a religiously based, collective will” and, consequently, since Islam is itself seen as fundamentalist in nature, “every believer will be made to follow its radical version” (Dyrendal 2020: 374). In this sense, the idea of ‘Islam’ is seen as being a uniting factor for all Muslims, that unites them “in a common plan for domination” (Ibid).

In this sense, the “Eurabia conspiracy theory has often become entangled in a more general opposition to immigration” (Bergmann 2021: 40), connected to political statements of failed integration (Ekman 2022: 1128) – which are based around the notion that Western societies are homogeneous, and that Muslims and other migrants are unable to integrate into them (Gualda 2021; Ekman 2022) – or to the notion that “incorporation of diversity, multiculturalism or other elements of Islam or the Muslim world into [Western] culture” will mean the total collapse of society, which will become a colony of Islam (Gualda 2021: 61-62). In other words, the arrival of “new norms, habits and customs brought by the foreign population […] could influence the disappearance of one’s own culture” (Ibid), turning immigration into an ‘invasion’ that threatens people’s identity.

So, what we have here, is first of all, a very problematic conflation between Arab world and Muslim world. The attribute of religious identity based on ethnic and geopolitic identity is a problem in itself. But let us take a quick step back.

Asbjørn Dyrendal (2020) describes these three kinds of dynamics that can be used to express the relationships between conspiracy theories and religion. The first one, conspiracy theories in religion, relate mostly to authority and power, since they are usually employed to delegitimize those that are seen as enemies of a certain religious group. The second one, conspiracy theory as religion, regards the idea that conspiracy theories are replacing religion by exerting its functions in a now more secularized society. This notion can be questioned, since it is first of all not possible to state that we have more conspiracy theories today than during a time when religious adherence was supposedly stronger, and also because “religion is usually not negatively correlated with conspiracy beliefs”, suggesting the two go hand-in-hand, rather than one replacing the other (Dyrendal 2020: 373). Instead of thinking of conspiracy theory as a substitute of religion, we may think of the ways in which conspiracy theory can be seen as a form of religion, given the status of both religion and conspiracy theories as alternative or counter-knowledge, as well as how they both organise collective identities on the basis of in-group and out-group.

But I want to focus on the last one, conspiracy theories about religion, or how conspiracy theories are formed regarding certain religious groups. Eurabia is an ethno-religious myth. As a researcher, I am aware of the complexities in these narratives and I obviously don’t buy this conflation between Arab and Muslim, but it is a matter of how the analysed discourse is constructed – the Emic point of view. To the endorsers of Eurabia discourse, there is no distinction, they don’t fear Christian Arabs. I would argue most of them don’t even know there is such a thing as Christian Arabs. They fear what they think Islam is (since they are also ignorant of the complexities of Islam itself). And of course there is another dimension to this issue which is the fact that conspiracy theories are not completely misaligned with the contexts that favour certain representations. These notions about the Arab world, Islam, and Muslims are not constructed in a vacuum. Media representations of Islam contribute to the construction of stereotypes in conspiracy theories as well.

FINAL REMARKS

So, in conclusion, the Eurabia conspiracy theory was brought firmly into the political mainstream by the financial crisis of 2008 and later the refugee crisis of 2015 (Bergmann 2021: 48-49). Nowadays, it is common to find political leaders who propagate Great Replacement and Eurabia conspiracy theories in the mainstream media (Ekman 2022: 1127). As we see such Islamophobic racist discourses become more popular, we also see them become normalized, especially across new media platforms such as Telegram. This means research needs to adapt to these new contexts, and digital humanities tools become invaluable for these efforts.

REFERENCES

Bergmann, E. (2021). The Eurabia conspiracy theory. In: Önnerfors, A., & Krouwel, A. (Eds.), Europe: Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe. Routledge, 36-53.

Dyrendal, A. (2020). Conspiracy Theory and Religion. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 304-316.

Ekman, M. (2022). The great replacement: Strategic mainstreaming of far-right conspiracy claims. Convergence, 28(4), 1127-1143.

Gualda, E. (2021). Metaphors of Invasion, Imagining Europe as Endangered by Islamisation. In: Önnerfors, A., & Krouwel, A. (Eds.), Europe: Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe. Routledge, 54-75.