This blog post consists in the transcription of a talk that Heidi presented at the “Objects, Technique, Meaning” seminar series, which took place at the semiotics research group from the University of Turin.

Right at the beginning of his article “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam?” (on page 2), Latour talks about “matters of fact” and “matters of concern”. Throughout the paper, he comes back to other concepts he has developed in his previous works, such as “artifacts”, “objects”, and “things”. I thought it would be interesting to start this seminar by expanding a bit on these notions, providing the text under discussion today with a bit of a background.

As we already know, Bruno Latour was extremely influential to the philosophy of science, and his body of work changed the way we see things on fundamental levels. His 2004 paper Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern characterize a paramount shift in his line of thought, and it’s one of my favourite texts. To understand the importance of this paper, I will briefly describe the place where Latour was coming from when he wrote it, starting with his 1979 book Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts (co-written with Steve Woolgar).

Laboratory Life investigates the processes involved in experimental science, attending to how such processes diverge from what is understood as ‘the scientific method’ (Latour; Woolgar 1979). For Latour and Woolgar, laboratorial science largely involves taking subjective decisions on whether to acknowledge what are mostly inconclusive data. The authors conclude that experimental science is a process of, not uncovering facts, but constructing them. Latour, then, goes on to develop what became known as Actor-Network Theory (Latour 2005), which states that discovery is contingent on the actors involved in its process (scientists, samples, equipment, institutions… and their interactions). The central thesis advanced until now, thus, regards how science produces in the laboratory new objects – which he calls artifacts; socially constructed facts – instead of discovering pre-existing ones from nature.

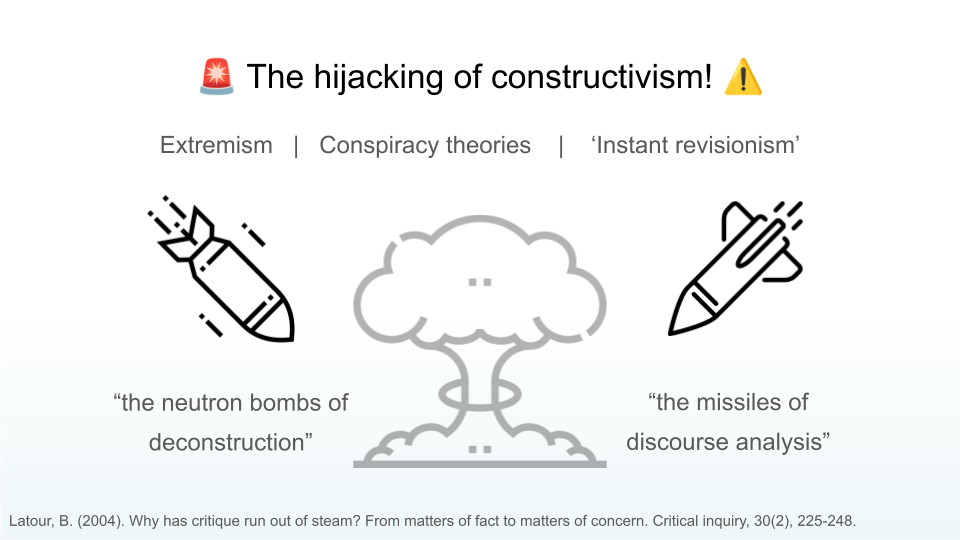

The view held by Latour regarding constructivism and criticism changed as he realized that the notions which he helped shape (mainly how ‘facts’ are only ideas stemming from ideological bias rather than incontrovertible truths) had been hijacked, in his words, by “dangerous extremists” who were using them to support conspiracy theories and dismiss hard-won solid evidence “that could save our lives” (Latour 2004, p. 227) – he calls this ‘instant revisionism’, saying that “the smoke of the event has not yet finished settling before dozens of conspiracy theories begin revising the official account” (ibid., 228). Latour states that, “of course conspiracy theories are an absurd deformation of our own arguments, but, like weapons smuggled through a fuzzy border to the wrong party, these are our weapons nonetheless”. So, how do we fight conspiracy theorists armed with “the neutron bombs of deconstruction” and “the missiles of discourse analysis”? (ibid., 230), Latour asks us.

His new proposal for science studies “is to be found in the cultivation of a stubbornly realist attitude” (ibid., 231), centred around the development of ideas instead of their debunking. On the paper, Latour suggests that science should occupy itself not with facts, but with matters of concern. The reason for that is because “matters of fact are a poor proxy of experience” (ibid, 245), as well as an “archaic representation of our real state of affairs” (Latour 2008, p. 39), or even “a confusing bundle of polemics, of epistemology, of modernist politics that can in no way claim to represent what is requested by a realist attitude” (Latour 2004, p. 245). As such, Latour suggests a new realist critical attitude which he calls ‘second empiricism’, arguing that his intent “was never to get away from facts but closer to them, not fighting empiricism but, on the contrary, renewing empiricism” (Latour 2004, p. 231).

Latour proposes that we move past this ‘first wave’ of empiricism (characterized by these ‘uninterpreted’ facts) towards a‘second wave’, founded on the plurality of modes of existence and respectful of the multiple interpretative keys, that is, the ways in which something can ontologically be understood as ‘true’ or ‘false’ (Latour 2013).

According to the author (Latour 2008, p. 34), when science limits itself to only dealing with matters of fact (being “objective”, decided by evidence, logic, statistics, etc.), scientific objects become highly artificial, a-historical, far-from-reality “pieces of dead material”. For Latour, there is no “harsh world made of indisputable matters of fact”, real and material, on the one hand, and “on the other, a rich mental world of human symbols, imaginations and values” (Latour 2008, p. 38). Such division does not exist in reality, so why should it exist in science? To achieve the end of such division (between real-material/symbols-values), Latour suggests that scientists should abandon matters of fact in detriment of matters of concern.

In a straightforward manner, a matter of concern is the amplification and contextualization of a matter of fact. While matters of fact are “distorted by the totally implausible necessity of being pure” and often “of no interest whatsoever” to society (Latour 2008, p. 47), matters of concern “overflow their boundaries” and “have to be liked, appreciated, tasted, experimented upon, mounted, prepared, put to the test” (ibid., 39). Most importantly, “matters of concern have to matter” (ibid., 47).

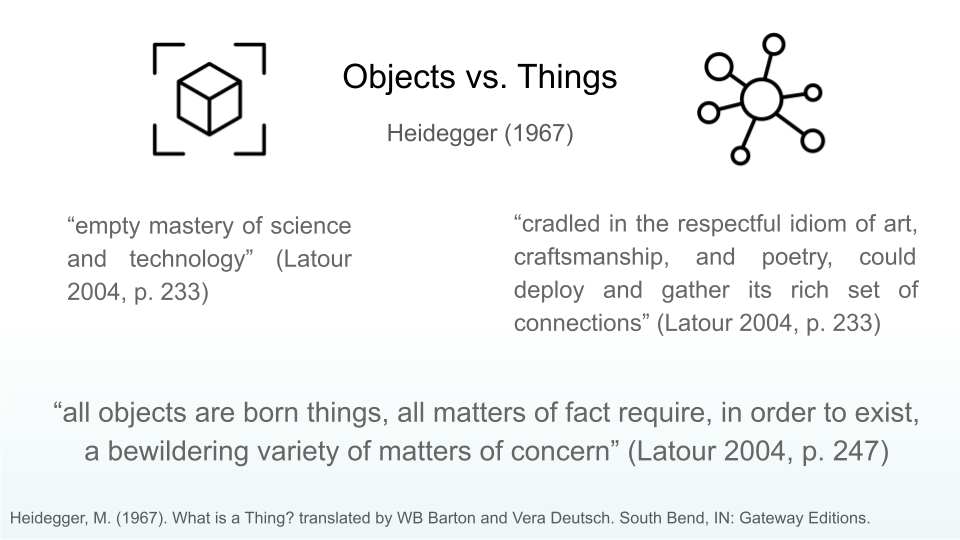

Borrowing the concept from Heidegger, Latour states that one word may designate matters of fact and matters of concern, and that word is thing. Latour, however, takes a very different approach towards the concept of ‘thing’ than its original author. Heidegger (1967) gives us an example, stating that a handmade jug can be a thing, while an industrial can of Coke is but an object. Latour writes: “while the latter is abandoned to the empty mastery of science and technology, only the former, cradled in the respectful idiom of art, craftsmanship, and poetry, could deploy and gather its rich set of connections” (Latour 2004, p. 233). Nevertheless, to Latour the object of science and technology has the same richness and complicated qualities of a Thing. To him, “all objects are born things, all matters of fact require, in order to exist, a bewildering variety of matters of concern” (ibid., 247).

While, from the point of view of constructivism, there is no such a thing as hard-facts (since all knowledge is socially constructed), concerning oneself purely with this narrow notion of objectivism and matters of fact is constricting. Existence is not divided between an external material and meaningless reality and a world of “psychic additions projected by the human mind” (2008, p. 36), and treating it as such is misguiding.

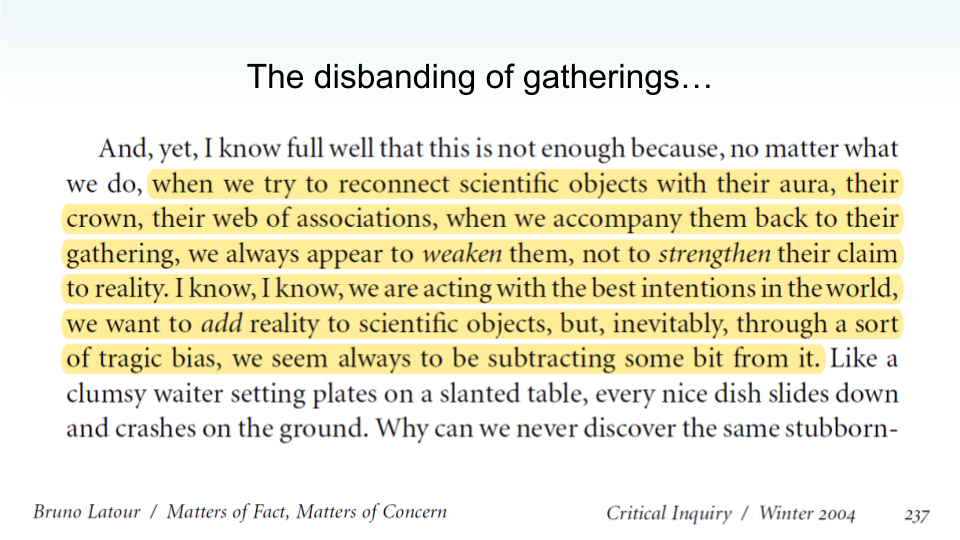

But then, a problem rises to our attention: “If a thing is a gathering [of connections], as Heidegger says, how striking to see how it can suddenly disband.” (Latour 2004, p. 235). As examples, Latour cites a couple of “former objects that have become things again” such as Climate Change, the hormonal treatment of menopause (ibid., 236), and other scientific matters under public contestation. The problem is that:

And here is where we return to the problem of how criticism has been deformed and how it’s affecting the world today, generating a ‘deconstructive hermeneutics’ (Leone 2017, 228), which responsible for the de-normalization of scientific expertise that we have been witnessing in online social media, and that generated a society “that does not provide itself with inter-subjective, rational patterns for the consolidation of interpretive habits” (Leone 2017, 228) – since this type of thinking takes any habit (or mainstream belief) as being an imposition of power (authority) that, in turn, needs to be dismantled. The consequence of this “is inevitably a chaotic society” where “conflicts constantly arise and are never recomposed” (Leone 2017, 228). So, how do we fix this?

Latour (2004, p. 248) asks: “What would critique do if it could be associated with more, not with less, with multiplication, not subtraction”. To achieve this, all entities need to cease being “objects defined simply by their inputs and outputs and become again things, mediating, assembling, gathering” more connections. He states: “If this were possible then we could let the critics”, or the deconstructivists, “come ever closer to the matters of concern we cherish, and then at last we could tell them: ‘Yes, please, touch them, explain them, deploy them’.”

References

Heidegger, M. (1967). What is a Thing? translated by WB Barton and Vera Deutsch. South Bend, IN: Gateway Editions.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts. Princeton University Press.

Latour, B. (2004). Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern. Critical inquiry, 30(2), 225-248.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oup Oxford.

Latour, B. (2008). What is the style of matters of concern. Two Lectures in Empirical Philosophy. Assen, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Van Gorcum.

Latour, B. (2013). An inquiry into modes of existence. Harvard University Press.

Leone, M. (2017). Fundamentalism, Anomie, Conspiracy: Umberto Eco’s Semiotics Against Interpretive Irrationality. In: Umberto Eco in his Own Words, edited by T. Thellefsen, and B. Sørensen, 221–229. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.