INTRODUCTION

Essentially, medical conspiracy theories “depict medical, science or technology-related issues as under the control of secretive and sinister organisations” (Lahrach, Furnham 2017: 89), advocating that malevolent “motivations underpin everything from vaccination campaigns to cancer treatment” (Grimes 2021: 1). Although Medical conspiracy theories have been “a problem since before the dawn of social media” (Ibid), it is unquestionable that the Internet has provided an amplification to this issue. Even before the pandemic, when the gravity of this problem became most evident (Ibid), the digital spread of disinformation had already shown alarming consequences for the acceptance of medical science, especially when it comes to anti-vax propaganda.

Already in 2019, the WHO (2019) declared “vaccine hesitancy” as one of the top-ten threats to global health. Since “Medical conspiracy theories directly contradict evidence-based scientific research” (Lahrach, Furnham 2017: 89), belief in this type of conspiracy theory leads people to reject modern mainstream medicine (Ibid; Douglas et al. 2019: 3), the consequences of which can be severely life-limiting and harmful (Grimes 2021:2). Under these circumstances, the case of the anti-vax movement is especially concerning, seeing how the online spread of disinformation contributed to the worldwide decrease of vaccine uptake, consequently leading to the comeback of diseases that had been virtually cured in the past (Douglas et al. 2019: 4; Grimes 2021: 2).

Many controversies led to the widespread of anti-vax conspiracy theories, ever since the very beginning when vaccines were first being developed. What eventually became one of the main pillars of the anti-vax movement was the publication of an article in 1998 by gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield that suggested a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine to the development of autism (Stano 2020: 488; Sherwin 2021: 559). Even though in the following years Wakefield’s research was investigated and found to be irresponsible, dishonest, and fraudulent (in the words of the UK General Medical Council), the anti-vax movement had already gained traction, so much so that by 2002 “immunisation rates dropped below 85 per cent” (Stano 2020: 489). Progressively, the phenomenon of the anti-vax movement “extended beyond Wakefield’s case, making social networks key actors in the rise and spread of forms of anti-vaccine conspiracionism online” (Ibid, 491). Social media has thus become, as frequently cited in academic studies, a “source of vaccine controversy” (Grant et al. 2015: 2). Thriving in this ambient, anti-vax conspiracy theories have become resilient, persisting despite all efforts to eradicate them, even progressively gaining more support.

Considering this relevance, this brief presentation aims to analyse social media posts with the help of digital humanities methodologies, seeking language patterns that can potentially assist in the codification of cultural meanings and in the formation of ideological clusters of anti-vaccine conspiracy theorists online.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unfortunately, I am unable to share the name of the Telegram group from which I obtained my data, as it is sensitive information protected by the GDPR. What I can say is that the group’s description states that it is an “Anti-New World Order” channel. The “New World Order” is a term that is common for many conspiracy theories which describe a secretly emerging authoritarian/totalitarian political elite that seeks to replace all sovereign nation states with a one-world government.

The data that I obtained from the group was the textual (non-pictorial) content of messages sent from its administrator to the channel’s subscribers (which are a total of 25.1 thousand accounts). Only messages containing the string of characters ‘vacc’ somewhere in its text were collected (thus including words such as ‘vaccine’, ‘vaccines’, ‘vaccination’, ‘anti-vaccine’, etc). Messages were collected from 1st July 2023 to 1st June 2024, manually, totalling 9 messages. My intention is to automate this process in the future, so that a larger amount of texts may be easily collected.

The data was compiled on a .txt file, which was then uploaded to Voyant – an open-source web-based text reading and analysis environment which was designed to facilitate reading and interpretive practices for digital humanities students and scholars.

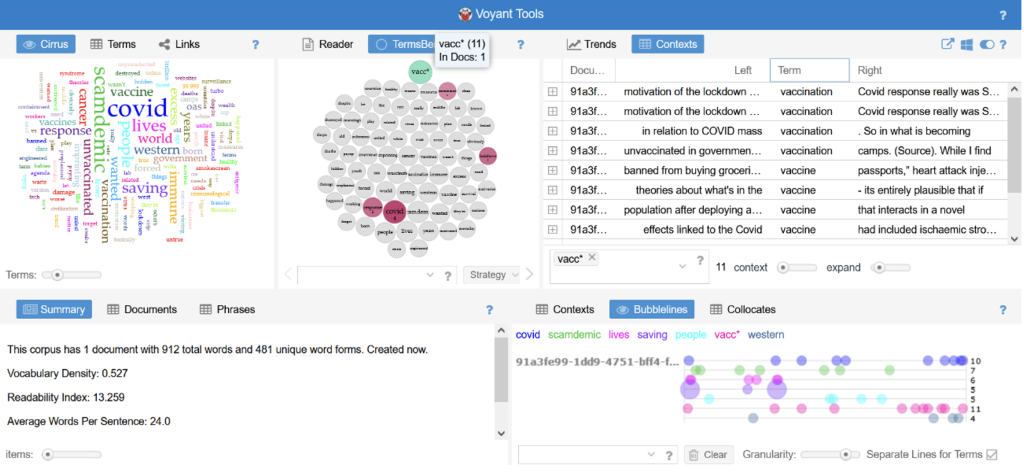

After uploading the dataset to Voyant, this is the panel I was working with:

PRELIMINARY RESULTS

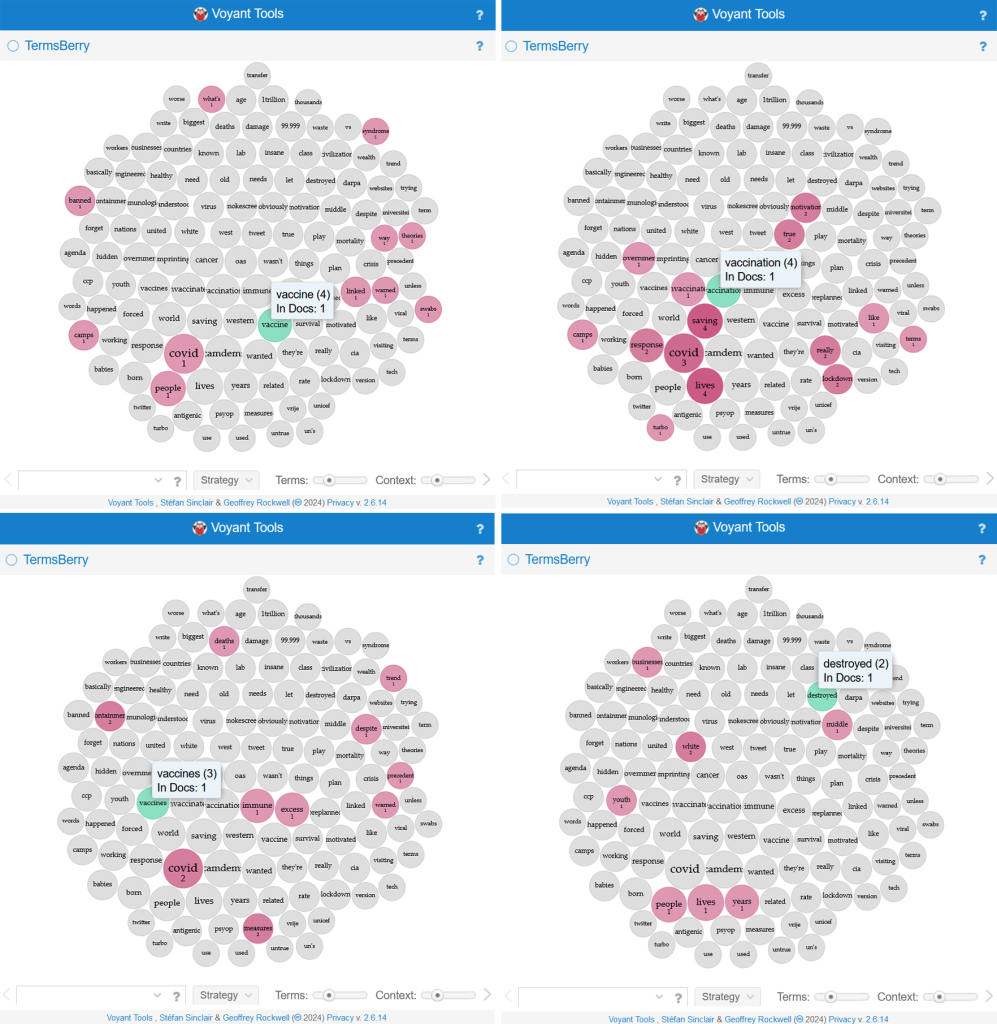

I explored some of Voyant’s available tools that could help me in identifying language patterns, starting with the ‘TermsBerry’, which shows the most common terms of the text and their closeness to each other:

By hovering the mouse over a term, the words that are closely related to it in the text light up. The stronger the colour, the more times these two terms appear together. For example, the strongest correlatives of ‘vaccines’ (figure on the bottom left) are: ‘containment’, ‘covid’, and ‘measures’, while weaker (but still relevant) correlatives are: ‘immune’, ‘excess’, ‘deaths’, and ‘trend’. The relevant correlatives for ‘vaccine’ (singular) (top left figure) are: ‘camps’ (alluding to the idea of ‘vaccination camps’), ‘banned’ and ‘people’ (connected to the victimization of nonvaccine individuals), ‘covid’, ‘linked’, ‘theories’, ‘warned’ (related to how conspiracy theories seek to warn people of dangers that only those capable of observing hidden connections can see), and ‘swabs’ (code for the act of ‘getting vaccinated’).

Interestingly, the strongest correlatives of ‘vaccination’ (top right) are: ‘covid’, ‘response’, ‘lockdown’, ‘true’, ‘motivation’, ‘saving’, and ‘lives’. Interpreting these results require caution. Do these relate to somehow the idea of vaccines as saving people’s lives? By looking at the correlatives of ‘destroyed’ it is possible to see: ‘businesses’, ‘white’, ‘people’, and ‘lives’. This tool does not provide for negation, which means that correlates will appear even if the meaning of the sentence is negative.

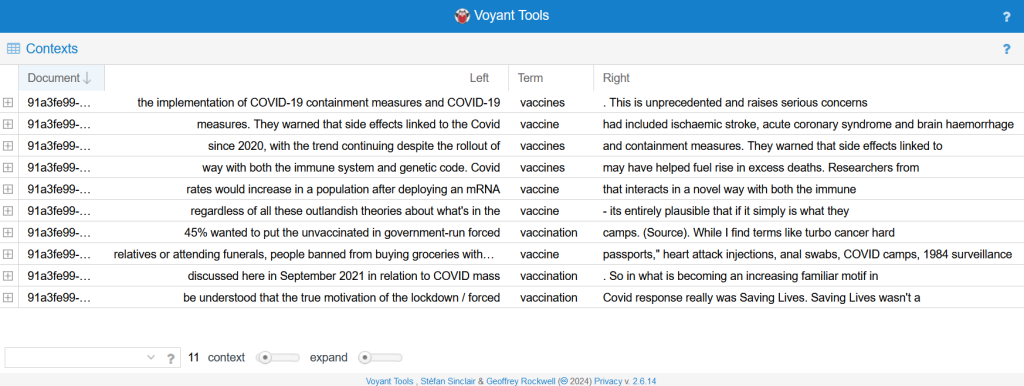

To investigate this further, we may take a look at another tool, called ‘Contexts’:

Here it is possible to see all occurrences of terms containing the string ‘vacc’ in the dataset as well as what precedes and what follows each occurrence in the text. Reading the context allows to confirm (or disproof) the analysis of the results of the correlatives, in a way that it is possible to be sure that the discourse in the texts do not see vaccines or the lockdown as measures taken to save lives, focusing instead on the side-effects and on the notion of these measures as being harmful. It is important to note that reading the context of each occurrence is only possible while dealing with such a small dataset (including only 11 occurrences from a total of 9 messages). The bigger the dataset, the more difficult it becomes to check the context for each analysed word and meaning.

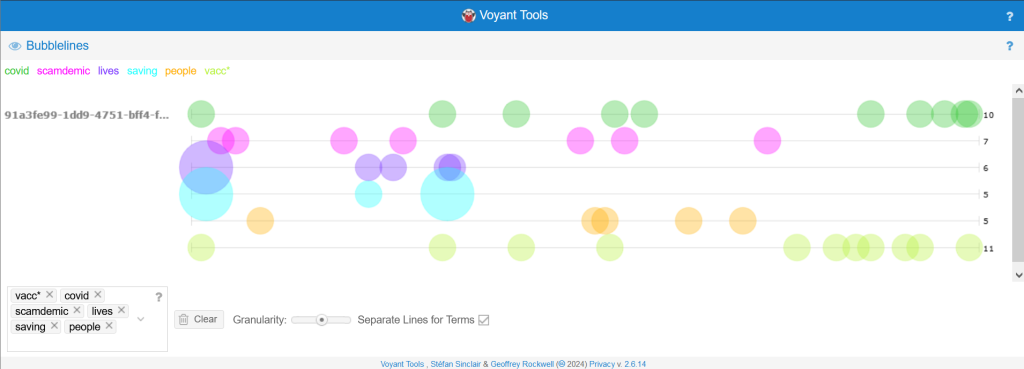

Finally, it is worth mentioning the tool ‘Bubblelines’:

This graph shows the occurrence of selected terms (in this case, ‘vacc*’, ‘covid’, ‘scandemic’, ‘lives’, ‘saving’, and ‘people’) over the course of the txt file – and, since it contains the messages in order of post, it also reflects passage of time. We can see that ‘covid’ (dark green) and ‘vacc*’ (light green) appear together most of the times, therefore the discourse surrounding vaccination in the channel mostly regards the covid vaccine and not other kinds. Considering the messages were collected between 2023 and 2024, one could suppose that would not necessarily be the case, and yet it appears so. Another interesting result points to the occurrences of the term ‘scandemic’ spread across the timeline, which I previously supposed it would coincide with the occurrences of Covid but that did not. Rather, the graph suggests the terms are used almost interchangeably, which may indicate that ‘scandemic’ is used as code for the ‘covid pandemic’.

DISCUSSION & FINAL REMARKS

One notion is commonly echoed in the literature: that conspiracy theories are strongly related to the complexities of living under conditions of uncertainty (mainly around values, morals, and identity), as well as fear and confusion that accompany these contemporary crisis-filled periods of socio-cultural upheavals, when epistemic conventions erode, in the risk-saturated, overly-connected, globalized world of late-capitalism (Douglas et al. 2019; Harambam 2020; Lee 2020; Butter & Knight 2020; Leone et al. 2020).

Medical conspiracy theories “are widely known, broadly endorsed, and highly predictive of many common health behaviours”, in a way that their belief “arises from common attribution processes” rather than from psychopathological conditions (Oliver, Wood 2014: 818). The anti-vax movement, more specifically, is not restricted to any single political inclination (Avramov et al. 2020: 521). Besides, it is possible to affirm that belief in medical conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy are not likely to be binary, but rather (much like radicalisation), exist “on a spectrum, which can be readily influenced by several mechanisms” (Grimes 2021: 2).

As meaning-making mechanisms, conspiracy theories reduce complexity, suggesting “simplistic and opaque relationships between causes and effects or inputs and outputs” (Önnerfors & Krouwel 2021: 254). This may seem paradoxical, since “some conspiracy theories appear complex on the surface”, possessing layers of interconnected elements and assumptions, however, “in the end most conspiracy theories make a relatively black-and-white assumption of an all-evil conspiracy stopping at nothing to pursue malevolent goals” (Krouwel & van Prooijen, 2021, p. 29). Producing its own evidence, they bring about coherence from a disordered social reality (Amlinger 2022: 262), establishing “a pseudo-rationality (particularly related to presumed causalities) while addressing emotions such as fear and blame within a simplified ethics of good and evil” (Önnerfors & Krouwel 2021: 254).

Therefore, it is possible to say that conspiracy theories carry out “epistemic search for hidden realities” aiming “to give meaning to the gaps in perception” through causal determination that is, however, incongruent with reality (Amlinger 2022: 264). This way, sense is “created in a situation of existential fragility”, where the feelings of powerlessness are warded off by the idea of taking back control (Steiner & Önnerfors 2018: 33), since “simple and straightforward beliefs about society foster people’s sense that they understand the world, which helps them regulate such negative feelings” (Krouwel & van Prooijen 2021: 29).

The dichotomic style of processing characteristic of conspiracy theories manifests inflexible convictions that are also innate to extreme political ideologies, leading to “a pessimistic view about the functioning of society, independent of whether it is extremism on the right or on the left” (Thórisdóttir et al. 2020: 307). According to Önnerfors and Krouwel (2021: 263), it is the “omnipresence of doom scenarios” and “absence of a positive political project for the future” that promote fertile ground for conspiracy belief.

As means of conclusion, considering this work is still in-progress, I can state that there are still methodological issues, namely the fact that as data amount increases, it becomes more difficult to avoid loss of context, opening the analysis for the possibility of misinterpretation. This is still a challenge that I am not sure how to resolve, however, I still believe there is much need for the development of such methodology, since when it comes to social media, scholars need to work with increasingly larger texts.

REFERENCES

Amlinger, C. (2021). Men make their own history: Conspiracy as counter-narrative in the German political field. In: Hristov, T., Carver, B., & Craciun, D. (Eds.), Plots: Literary Form and Conspiracy Culture. Routledge, 179-199.

Avramov, K., Gatov, V., & Yablokov, I. (2020). Conspiracy theories and fake news In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 512-524.

Butter, M. & Knight, P. (2020). Introduction. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 304-316.

Douglas, Karen; Uscinski, Joseph; Sutton, Robbie; Cichocka, Aleksandra; Nefes, Turkay; Siang Ang, Chee; Deravi, Farzin 2019. Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Political Psychology 40 (2019): 3-35.

Grant, L., Hausman, B. L., Cashion, M., Lucchesi, N., Patel, K., & Roberts, J. (2015). Vaccination persuasion online: a qualitative study of two provaccine and two vaccine-skeptical websites. Journal of medical Internet research, 17(5), e133.

Grimes, David 2021. Medical Disinformation and the Unviable Nature of COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories. PLoS ONE 16(3): e0245900, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245900

Harambam, J. (2020a). Conspiracy Theory Entrepreneurs, Movements and Individuals. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 278-291.

Krouwel, A., & van Prooijen, J. W. (2021). The new European order? Euroscepticism and conspiracy belief. In: Önnerfors, A., & Krouwel, A. (Eds.), Europe: Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe. Routledge, 22-35.

Lahrach, Y.; Furnham, A. (2017). Are modern health worries associated with medical conspiracy theories?. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 99, 89-94, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.004

Lee, B. (2020). Radicalisation and conspiracy theories. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 304-316.

Leone, M., Madisson, M., & Ventsel, A. (2020). Semiotic Approaches to Conspiracy Theories. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 43-55.

Oliver, E. & Wood, T. (2014). Medical Conspiracy Theories and Health Behaviors in The United States. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(5), 817-818.

Önnerfors, A., & Krouwel, A. (2021). Between Internal Enemies and External Threats; How conspiracy theories have shaped Europe – an introduction. In: Önnerfors, A., & Krouwel, A. (Eds.), Europe: Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe. Routledge, 1-21.

Sherwin, B. D. (2020). Anatomy of a conspiracy theory: Law, politics, and science denialism in the era of COVID-19. Tex. A&M L. Rev., 8, 537.

Stano, S. (2020). The Internet and The Spread of Conspiracy Content. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 483-496.

Steiner, K., & Önnerfors, A. (2018). Expressions of Radicalization. Global Politics, Processes and Practices.

Thórisdóttir, H., Mari, S., & Krouwel, A. (2020). Conspiracy theories, political ideology and political behaviour. In: Butter, M., Knight, P. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories. Routledge, 304-316.

One reply on “Presentation at the 3rd International Conference of PACT (Populism and Conspiracy Theory Project)”

[…] In this panel, I had the opportunity to hear my colleague Heidi Piva‘s presentation on radicalization processes in European Telegram groups, on which she wrote an interesting blog post. […]