Within the VORTEX Doctoral Network, we explore three key dimensions of radicalisation: (1) Pathways of Radicalisation, (2) the Social and Political Contexts of Radicalisation, and (3) Countering Radicalisation. Some time ago, those of us working on the Social and Political Contexts of Radicalisation decided to organise a panel to share our research with fellow scholars, practitioners, and the broader civil society. Last week, Heidi Campana Piva, Violette Mens, and I brought that idea to life at the 5th Helsinki Conference on Emotions, Populism, and Polarised Politics (HEPP5), hosted by the University of Helsinki.

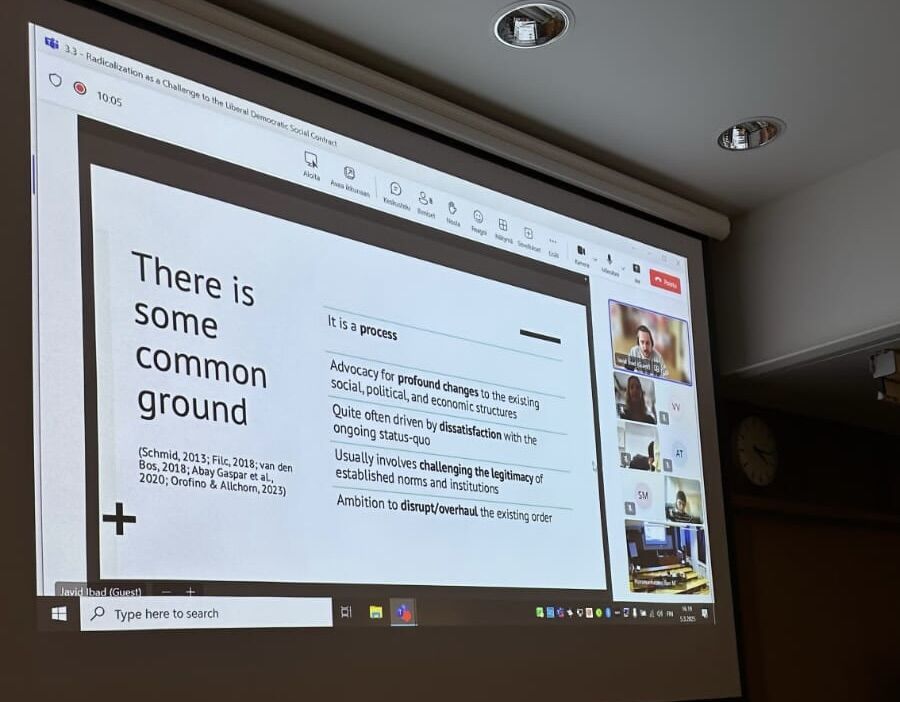

Our panel, Radicalisation as a Challenge to the Liberal Democratic Social Contract, examined how radicalisation fractures liberal democracy across societal, epistemic, and political domains—through conspiracy-fuelled extremism, the research-policy divide, and the mainstream right’s illiberal drift.

Heidi presented her research on the anti-establishment sentiments embedded in conspiracy theories and their role in radicalisation. She argued that conspiracy theories do more than reflect societal tensions—they actively accelerate radicalisation. By demonising enemies, silencing dissent, and framing violence as a necessary wake-up call, they don’t merely spread counter-knowledge; they weaponise it. Her research offers crucial insights into how rising social pressures may erode liberal democracies.

Violette, in turn, took a more applied approach, analysing France’s epistemic community on radicalisation research. As radicalisation studies expand, a stark divide persists between academic insights and political action, often fuelling populist and polarising responses. Her work explores how France’s dual-role researchers—those who straddle academia and policymaking—shape radicalisation discourse, revealing how knowledge translation impacts both the social contract and its fractures.

Finally, I tackled the political dimension by examining the illiberal turn in European (and global) politics—a shift that could reshape liberal democracies for years to come. My central question: Is the mainstream right radicalising? While European mainstream right parties have long radicalised on immigration, is this trend expanding into other policy domains? As far-right parties broaden their battlegrounds, I conceptualise how policymaking functions in liberal versus illiberal democracies and explore whether mainstream right-wing parties are adopting illiberal policymaking strategies. I also outline key areas for future research.

Radicalisation is not just a phenomenon confined to fringe movements or extremist networks—it is reshaping the very foundations of democratic governance. Understanding these dynamics is more urgent than ever. Our panel was just one step in this broader conversation, and the work continues.

Please have a look on my presentation here: